Some time ago, I achieved a state of Zen: I came to enjoy and deeply love The Simpsons rather than "merely" respecting it as the American institution that it was.

See, when it comes to entertainment, I can easily divorce respect from love, without taking away from one or the other. I've never disliked The Simpsons except for a stupid phase in junior high, but I've never felt any deep emotional attachment to it, either.

Like most North Americans, The Simpsons has been a staple of my life from toddlerhood onward: I can name almost every character, identify every quote and catchphrase, and it seems like I have seen most of the older episodes a billion times, so I'm not sure what alchemical qualities combined to let me make it to my mid- 20's without gaining a real deep affection for The Simpsons.

I used to eagerly follow the show in my pre-teendom, then went through a shameful phase where I turned up my nose at all cartoons which weren't overtly fantastical, and then another phase where I absolutely hated watching newer episodes because they seemed garish and harsh, and then finally settling down into a state where I just watched older reruns of The Simpsons time and time again, not getting into it, but not really wanting to change the channel.

But it's true now that I really love and appreciate The Simpsons rather than just considering it an eternal object in my environment. That feeling that the newer episodes are awful and not worth my time has carried over, and even when others say the series is getting its magic back, I can't return the favour (I didn't like the movie, for instance). My current cut-off point is around Season 8 or 9, but I might re-think that.

What's the core strength of The Simpsons have been repeated ad nauseum, but there the are: being funny on multiple levels, being clever on multiple levels, being developed while still having little real continuity, and being at its best when there is some genuine feeling for the dysfunctional family. The later seasons feel like they've lost all their warmth, so that even when they may be equally clever and challenging, they don't have the same magic as the older episodes.

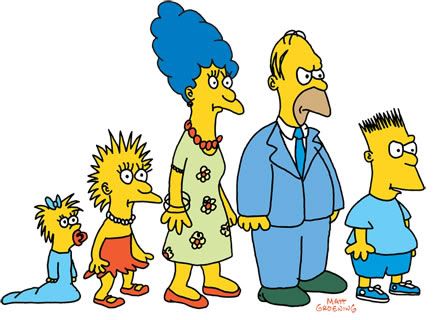

And just like with the first volume of The Sandman, I find the first season of The Simpsons enjoyable to watch even as other, more involved fans dismiss it as just a test drive. In both cases, there is a certain charm to the lack of sophistication seen in the beginnings of a great work, the contrast between it and what it later became, but at the same time, there's enough of the series' core strengths emerging that the early works are enjoyable for their own sake.

Also, I now declare that any nerds discussing "good American cartoons" must put The Simpsons on their list, instead of being dismissive of comedies or animated sitcoms by reflex. I know guys, I was there once too: but an animated series doesn't have to be a an action drama with moral ambiguity and strong continuity in order to be "good".

It's easy to name who would be my favourite characters in the series: Homer and Lisa Simpson, both of whom are also are also in some ways difficult characters for me to like.

Cliches can transcend their roots to feel special and original to an individual viewer, and several critics have made a strong case for the members of the Simpson family being able to achieve that, but part of me still bridles at the archetypes that both Homer and Lisa represent.

Others more cutting than me have wrestled with the issue, but I tend to agree with those who belive that the "bumbling dad" character type also does males some favours in perpetuating the idea that they are helpless and need to be coddled and catered to. But my problems with Homer are larger than that: in a way, he's the embodiment of a whole bunch of general male wish fulfillment theories: that he can be silly and wacky and self-indulgent and we'll love him for it, and Marge, being the female, has to remind him of morals and social obligations. While Marge might be easier to get along with in the real world, it's Homer who's ultimately more fun and appealing. You can see this dynamic played out in a lot of other cartoons which are very different from The Simpsons.

Homer was a really great and fun character before "jerkass Homer" syndrome set in, but that aspect of him can't totally be glossed over by ironic satire or moral sophistication. Yes, of course the writers knew when to dial back Homer's self-indulgence to show there are lines he won't cross (a technique which is beloved by cartoon male Id-dom but that "jerkass Homer" avoids), but the idea that appealingly self-indulgent = male remains.

Just like Homer, all the other fictional characters who amuse me because of their naked displays of Id have been male, and it bothers me a bit, the suggestion that female characters can't be funny, strange, quirky, interesting, or self-indulgent, at least and not have it treated the same way. A female character would be more likely to be judged harshly for blatantly pursuing crazy schemes or creature comforts, instead of being a hero.

With Lisa, she emobdies the opposite side of that notion: that women are to serve as the moral centre of a story, which is more of a burden than a lionization.

But I also wince a little bit when Lisa depicts a nerd's persecution fantasy, and feel a tad guilty about that, because I've been the Lisa Simpson in my life, so why I should feel uncomfortable, even a little contemptuous, with depictions of this kind of thing is...I don't know, a weird kind of self-hate. Especially since the series is also capable of taking the piss out of Lisa at one point or another.

And it also bothers me, even though it might have happened largely for the purpose of satire, that Lisa developed to fit that kind of generic "package" of what a progressive should be in terms of their outside habits, things that have nothing to do with how progressive a person is, but seem to have become required. Of course the politically progressive Lisa is a vegetarian, a Buddhist, and likes jazz. Those are, somehow, the interests and leanings that socially liberal people are "supposed" to have.

But at the same time, it's impossible to miss that Lisa has a lot of values and beliefs that I can get behind, and I appreciate intellectual characters as much as Id-driven ones (one day I hope to meet or create one who combines them both).

I've also recently read Chris Turner's book Planet Simpson, which seems to finally be making its round on the remaindered and used book store circuit. It was a great read, and helped to articulate and elevate the true power of The Simpsons, though I disagreed with him on a few points, and he'd likely find ways to disagree with me on any criticisms of Homer and Lisa...in Turner's eyes, the characters seem to be fully above such concerns, able to totally transcend the problematic cliches which they sprang from, if only through mocking them. But even a great show like The Simpsons isn't above the spirit of its times, and even a great show involves earnest but unexamined assumptions.

No comments:

Post a Comment